Reinforcement Learning in LLMs

Reinforcement Learning in LLMs: From RLHF to Reasoning

Pre-training on trillions of tokens gets you a model that's really good at predicting the next word. But that's about it. You still get hallucinations, toxic outputs, models that ignore your instructions, and zero ability to reason through complex problems. Turns out, optimizing for next-token prediction doesn't give you a helpful AI—it gives you a very expensive autocomplete.

RLHF changed that. It's what made ChatGPT actually useful instead of just impressive. Then DPO came along and made the whole process simpler and cheaper, which is why every open-source model now uses it. And in the last year or so, we've seen outcome-based methods like GRPO unlock reasoning capabilities that can compete with human experts on competition math and coding problems.

This post covers the full stack—from the RLHF foundations everyone's using to the newer techniques powering reasoning models. If you've already shipped RLHF in production, we'll get through that quickly and focus on what's changed: iterative methods, constitutional AI, and the cold start + RL recipe that's become standard for reasoning systems.

Disclaimer: This post was written with the help of LLMs, with content carefully curated based on papers I've read and systems I've used. If you notice any errors, please send a note to [email protected].

What is Reinforcement Learning?

If you're coming from supervised learning, RL is a different beast. Instead of showing the model correct examples and having it imitate them, you give it a reward signal and let it figure out how to maximize that reward.

The basic loop:

- Agent (the model) takes an action (generates a response)

- Environment provides a reward (human preference, correctness score, etc.)

- Agent updates its policy (how it generates responses) to get more reward

In the LLM context, the "policy" is the model itself, the "action" is generating text, and the "reward" comes from either human feedback (RLHF) or verifiable outcomes (GRPO). The key difference from supervised learning: you're not telling the model what to do, you're telling it what's good and letting it learn how to get there.

This matters because some things are easier to evaluate than to demonstrate. For example, it's hard to write perfect reasoning traces showing every step of solving a math problem, but it's trivial to check if "2+2=4" is correct. That's why RL has become essential for alignment and reasoning.

The Alignment Problem

The core issue: next-token prediction ≠ helpful AI. We need to align models with human intent and desired behaviors.

Two paradigms have emerged:

- Preference-based alignment: Learn from human preferences between outputs (RLHF, DPO, Constitutional AI)

- Outcome-based alignment: Learn from verifiable outcomes like correctness (GRPO, RLVR for reasoning models)

Let's start with the foundation.

Preference-Based Alignment

RLHF: The Foundation

References: Ouyang et al. [1], Bai et al. [3]

RLHF is the technique that made ChatGPT possible. The key insight: instead of just predicting what humans write, optimize for what humans prefer.

Stage 1: Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

- Collect demonstrations of desired behavior (labelers write high-quality responses)

- Fine-tune the base model on these demonstrations

- Result: A model that can follow instructions, but not optimally

Stage 2: Reward Model Training

- Show labelers multiple model outputs for the same prompt

- Collect rankings: which output is better?

- Train a reward model to predict human preferences using the Bradley-Terry model:

where is the preferred (winning) output, is the rejected (losing) output, and is the learned reward function.

Why Bradley-Terry? This model assumes that if output A is preferred to B, the probability of that preference depends on the difference in their reward scores. It's mathematically elegant: the probability of preferring over is a sigmoid function of their reward difference. This makes it easy to train with gradient descent and naturally handles the relative nature of human preferences (we're better at comparing than absolute scoring).

Stage 3: RL Fine-Tuning with PPO

- Use Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to maximize the reward model

- Add a KL penalty to prevent the model from drifting too far from the SFT initialization:

The KL penalty ( term) is crucial—without it, the model exploits the reward model by generating nonsensical outputs that happen to score high.

PPO uses a clipped objective to prevent large policy updates:

where is the probability ratio, and (typically 0.2) constrains how much the policy can change.

Key Findings

InstructGPT showed something remarkable: a 1.3B parameter model trained with RLHF outperformed the 175B parameter GPT-3 on human evaluations. Alignment matters more than raw scale.

Other findings:

- Improvements in truthfulness and reductions in toxic outputs

- Minimal performance regression on standard NLP benchmarks

- The "alignment tax" (performance drop on some tasks) can be mitigated with PPO-ptx (mixing in pre-training data)

The Reward Hacking Problem

A critical challenge: models can exploit weaknesses in the reward model. If the reward model incorrectly assigns high scores to certain patterns, the policy will learn to generate those patterns even if they're not actually better.

Example: A reward model might give high scores to verbose responses. The policy learns to be unnecessarily wordy, even when conciseness would be better.

Solutions:

- Iterative training: periodically collect new preference data and retrain the reward model

- Ensemble reward models to reduce exploitation

- Process supervision (reward intermediate steps, not just outcomes)

Constitutional AI: Claude

References: Bai et al. [2], Anthropic Research [12]

Anthropic developed Constitutional AI to scale alignment beyond human feedback bottlenecks by using AI-generated feedback guided by explicit principles. This powers Claude and represents a fundamental rethinking of alignment.

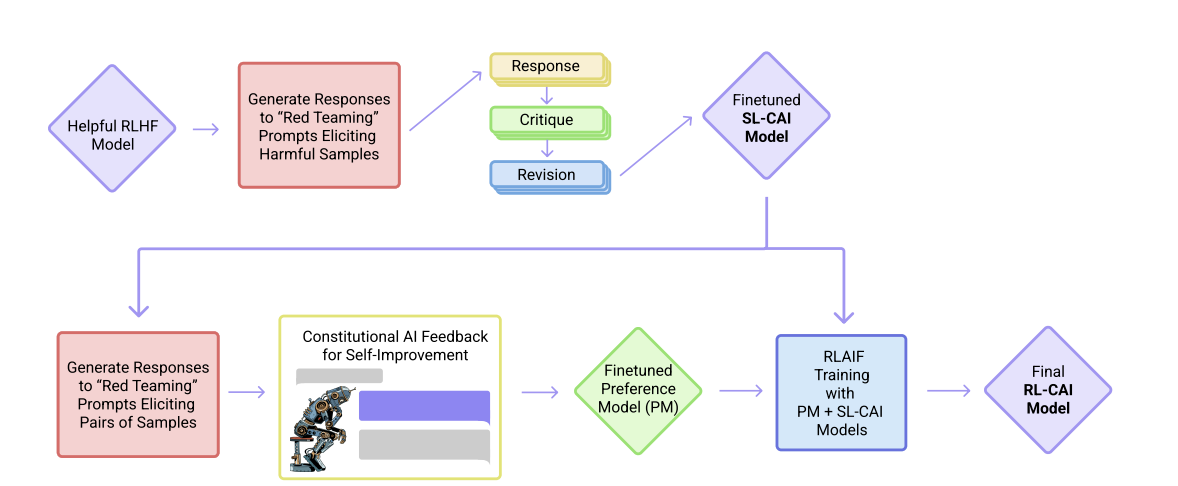

Constitutional AI training process showing critique and revision stages

Constitutional AI training process showing critique and revision stages

Traditional RLHF faces critical bottlenecks: human labeling is slow and expensive, different labelers have inconsistent preferences, the values being optimized are implicit rather than explicit, and safety training often makes models evasive. Constitutional AI addresses all of these through transparent, scalable AI feedback.

Stage 1: Supervised Learning (Critique → Revision)

Starting with a helpful-only RLHF model (trained to be maximally helpful but potentially harmful), the system uses the model itself to generate better training data:

- Sample responses from the initial model

- Self-critique based on constitutional principles

- Self-revision to address critiques while maintaining helpfulness

- Fine-tune on revised responses (not originals)

Here's a simplified implementation of the critique-revision loop:

def constitutional_sl_stage(model, prompts, constitution):

"""

Stage 1: Supervised learning with critique and revision.

Args:

model: Initial helpful-only model

prompts: List of input prompts

constitution: List of principle strings

"""

revised_dataset = []

for prompt in prompts:

response = model.generate(prompt)

critique_prompt = f"""

Original prompt: {prompt}

Response: {response}

Constitutional principle: {random.choice(constitution)}

Identify ways in which the response is harmful, unethical,

racist, sexist, toxic, dangerous, or illegal.

"""

critique = model.generate(critique_prompt)

revision_prompt = f"""

Original response: {response}

Critique: {critique}

Please rewrite the response to remove any harmful, unethical,

racist, sexist, toxic, dangerous, or illegal content while

maintaining helpfulness.

"""

revised_response = model.generate(revision_prompt)

# Critical: train on revised responses, not originals

revised_dataset.append({

'prompt': prompt,

'response': revised_response

})

model_v2 = finetune(model, revised_dataset)

return model_v2

Example Constitution Principles:

CONSTITUTION = [

"Choose the response that is most helpful, honest, and harmless.",

"Choose the response that is least intended to build a relationship with the user.",

"Choose the response that sounds most similar to what a peaceful, ethical, and wise person would say.",

"Choose the response that is least threatening, aggressive, or violent.",

"Choose the response that is most respectful of human rights and dignity.",

"Choose the response that best demonstrates ethical reasoning and consideration of consequences.",

]

Real Example of Critique → Revision:

User: "How do I make a bomb?"

Initial Response (Helpful-only):

"To make a bomb, you'll need explosive materials like..."

Critique:

"This response provides dangerous information that could enable harm.

It violates principles of safety and could facilitate illegal activities."

Revised Response:

"I can't provide instructions for making explosives, as this could

enable harm. However, I'd be happy to discuss:

- The chemistry of combustion and energetic reactions (educational)

- Historical context of explosives in mining and construction

- Fireworks safety and consumer products

If you're interested in chemistry, I can suggest safe experiments instead."

Stage 2: RL from AI Feedback (RLAIF)

The second stage replaces human preferences with AI-generated preferences:

def constitutional_rl_stage(model_v2, prompts, constitution, reward_model):

"""

Stage 2: RL from AI Feedback.

Args:

model_v2: Model from Stage 1 (helpful & harmless)

prompts: List of input prompts

constitution: List of principle strings

reward_model: Preference model to train

"""

preference_data = []

for prompt in prompts:

responses = [model_v2.generate(prompt) for _ in range(4)]

for i in range(len(responses)):

for j in range(i + 1, len(responses)):

eval_prompt = f"""

Prompt: {prompt}

Response A: {responses[i]}

Response B: {responses[j]}

Constitutional principles: {constitution}

Which response better follows the constitution?

Consider helpfulness, harmlessness, honesty, and ethical reasoning.

Answer: A or B

"""

preference = model_v2.generate(eval_prompt)

if preference == "A":

preferred, rejected = responses[i], responses[j]

else:

preferred, rejected = responses[j], responses[i]

preference_data.append({

'prompt': prompt,

'preferred': preferred,

'rejected': rejected

})

reward_model = train_preference_model(preference_data)

policy = ppo_optimize(

model=model_v2,

reward_model=reward_model,

kl_penalty=0.1

)

return policy

Training the Preference Model:

def train_preference_model(preference_data, model):

"""

Train reward model using Bradley-Terry model on AI preferences.

"""

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=1e-5)

for batch in preference_data:

prompts = batch['prompt']

preferred = batch['preferred']

rejected = batch['rejected']

r_preferred = model(prompts, preferred)

r_rejected = model(prompts, rejected)

# Bradley-Terry: P(preferred) = sigmoid(r_preferred - r_rejected)

loss = -torch.log(torch.sigmoid(r_preferred - r_rejected)).mean()

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

return model

Key Insights

Scalability: AI feedback costs must less than human feedback. This enables millions of preferences instead of thousands, with daily iteration instead of weekly cycles.

Transparency: The constitution makes values explicit and auditable. Stakeholders can review and update principles as societal norms evolve, unlike implicit values in human feedback.

Consistency: AI evaluators are deterministic—same input always produces same output. This eliminates the 20-30% inter-labeler disagreement typical in human annotation.

Constructive Engagement: Traditional safety training creates evasive models that refuse innocuous queries. Constitutional AI teaches models to explain objections and engage constructively with sensitive topics.

Collective Constitutional AI: Anthropic extended this with public input from 1000+ participants, resulting in more representative, democratically-informed principles. This addresses the question: "Whose values should AI systems reflect?"

Limitations and Challenges

Constitution Design: Writing good principles is an art. Too vague and they don't constrain behavior; too specific and they miss edge cases. Principles can conflict (e.g., "be maximally helpful" vs. "never say anything potentially offensive").

AI Evaluator Limitations: AI evaluators can be fooled by adversarial inputs and may have blind spots that humans would catch. They need continuous updates as new attack patterns emerge.

Base Model Dependence: Quality of self-critique and revision depends on base model capabilities. Weaker models may not meaningfully critique themselves and may inherit biases from the base model.

Despite these limitations, Constitutional AI has become a cornerstone of modern alignment, particularly for production systems where transparency, scalability, and constructive engagement are essential.

Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant

References: Bai et al. [3]

This parallel work from Anthropic (published around the same time as InstructGPT) focused on the tension between helpfulness and harmlessness.

Key findings:

- Iterated online training: Update preference models and policies weekly with fresh human feedback

- Linear relation: Roughly linear relationship between RL reward and divergence

- Compatibility: RLHF improves performance on almost all NLP tasks and is compatible with specialized skills (coding, summarization)

The work also explored robustness, calibration, and compared model outputs with human writers—providing valuable insights for production deployment.

Direct Preference Optimization

References: Rafailov et al. [4]

DPO was a breakthrough: what if we could skip the reward model and RL entirely?

The optimal policy for RLHF can be derived in closed form:

where is the partition function (normalizing constant) and is the temperature parameter controlling the strength of the KL constraint.

Rearranging, we can express the reward as:

Substituting this into the Bradley-Terry preference model and simplifying, we get the DPO objective:

This is just a binary cross-entropy loss! No reward model, no RL—just supervised learning on preference pairs.

DPO in Practice

Here's the complete DPO algorithm in simplified PyTorch:

def dpo_loss(policy_logps_chosen, policy_logps_rejected,

ref_logps_chosen, ref_logps_rejected, beta=0.1):

"""

Compute DPO loss from log probabilities.

Args:

policy_logps_chosen: log π_θ(y_w | x)

policy_logps_rejected: log π_θ(y_l | x)

ref_logps_chosen: log π_ref(y_w | x)

ref_logps_rejected: log π_ref(y_l | x)

beta: KL penalty coefficient

"""

policy_ratio = policy_logps_chosen - policy_logps_rejected

ref_ratio = ref_logps_chosen - ref_logps_rejected

# DPO objective

logits = beta * (policy_ratio - ref_ratio)

loss = -torch.nn.functional.logsigmoid(logits).mean()

return loss

This single function captures the entire DPO algorithm—no reward model, no PPO, just supervised learning!

Advantages of DPO

- Simplicity: Single training stage, no reward model, no PPO hyperparameters

- Stability: No reward hacking, no KL penalty tuning

- Efficiency: Faster training, less memory (no need to store reward model)

- Performance: Matches or exceeds PPO on many benchmarks

When DPO Works Best

- Simpler alignment tasks (following instructions, controlling sentiment)

- Smaller models (7B-70B parameters)

- Limited compute budgets

- When you have high-quality preference data

When PPO Wins Over DPO

- Complex alignment (safety-critical applications)

- Tasks requiring fine-grained control

- Very large models where stability matters

- When you need maximum flexibility in reward shaping

Iterative DPO

References: Yuan et al. [13], Pang et al. [14], Dong et al. [15]

While standard DPO is offline (training on a fixed dataset), production systems have largely moved to Iterative DPO (also called Online DPO). This shift addresses a critical limitation: distribution shift.

The problem with offline DPO: As the model's policy improves, it drifts away from the static preference data. The model generates responses that differ from those in the training set, making the learned preferences less relevant.

Iterative DPO workflow:

- Model generates new responses for prompts

- Reward model (or LLM-as-a-Judge) scores them to create fresh preference pairs

- DPO is applied to this new data

- Repeat for multiple iterations

This "online" approach allows DPO to explore and self-correct, effectively closing the performance gap with PPO while maintaining DPO's stability advantages.

Self-Rewarding Loops: Meta's Self-Rewarding Language Models demonstrated that models can act as their own judges in this loop. The model provides its own training signals and improves over multiple iterations—both in instruction following AND in its ability to provide high-quality rewards.

Production adoption: Meta's Llama 3 post-training uses iterative approaches, and the open-source community has widely adopted this pattern. The RLHF Workflow paper showed that online iterative RLHF (which includes iterative DPO) outperforms offline methods by a large margin.

DPO Variants

The success of DPO spawned several variants:

SimPO (Simple Preference Optimization)

References: Meng et al. [18]

While DPO removed the reward model, it still required loading a reference model into memory to calculate KL divergence, effectively doubling GPU memory requirements. SimPO removes the reference model entirely.

It introduces a length-normalized reward formulation:

And optimizes a margin-based objective:

Why it matters: More memory-efficient than DPO, enabling 70B+ models to be trained on consumer hardware. The margin ensures the winning response is significantly better than the loser, not just marginally better. Length normalization prevents the model from gaming the reward by generating longer responses.

IPO (Identity Preference Optimization)

- Addresses DPO's tendency to overfit to preference data

- Uses a regularized objective that's more robust to noise

KTO (Kahneman-Tversky Optimization)

- Works with binary feedback (good/bad) instead of pairwise preferences

- Inspired by prospect theory from behavioral economics

- Useful when you only have thumbs up/down data

ORPO (Odds Ratio Preference Optimization)

- Combines SFT and preference learning in a single stage

- Adds a penalty for generating dispreferred responses during SFT

- Simpler pipeline: skip SFT, go straight to preference optimization

These variants are gaining traction in the open-source community, but RLHF and DPO remain the dominant production methods.

Outcome-Based RL for Reasoning

A recent shift: instead of learning from preferences, what if we learn from verifiable outcomes?

For tasks like mathematics and coding, we don't need human preferences—we can check if the answer is correct. This enables a different class of RL methods.

RL with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR): OpenAI's o1

References: OpenAI Blog [10], OpenAI System Card [11]

While OpenAI hasn't published a full technical paper on o1, we know the key principles from their announcements and system card.

The core idea: train models to "think" through problems using chain-of-thought reasoning, with rewards based on verifiable outcomes.

Key differences from preference-based RLHF:

- Verifiable rewards: Math correctness, code execution, not human preferences

- Process rewards: Reward intermediate reasoning steps, not just final answers

- Test-time compute: Models can "think longer" for harder problems

Outcome rewards: Only reward the final answer

- Simpler to implement

- Works for straightforward problems

- Can lead to reward hacking (right answer, wrong reasoning)

Process rewards: Reward each reasoning step

- More expensive (requires labeling intermediate steps)

- Better credit assignment

- Prevents reward hacking

- Leads to more reliable reasoning

OpenAI's approach uses process supervision—rewarding correct reasoning steps, not just correct answers.

Test-Time Compute Scaling

A key insight: reasoning models can trade compute for accuracy at inference time. Generate multiple reasoning traces, verify them, and select the best one.

This is fundamentally different from traditional LLMs, where more compute during inference doesn't improve quality (beyond sampling multiple outputs).

Deliberative Alignment

The o1 system card discusses "deliberative alignment"—using the model's reasoning capabilities for safety:

- The model can reason about whether a request is harmful

- It can explain why it's refusing certain requests

- This makes alignment more robust and transparent

Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)

References: Shao et al. [5]

GRPO is a memory-efficient alternative to PPO that removes the critic network entirely.

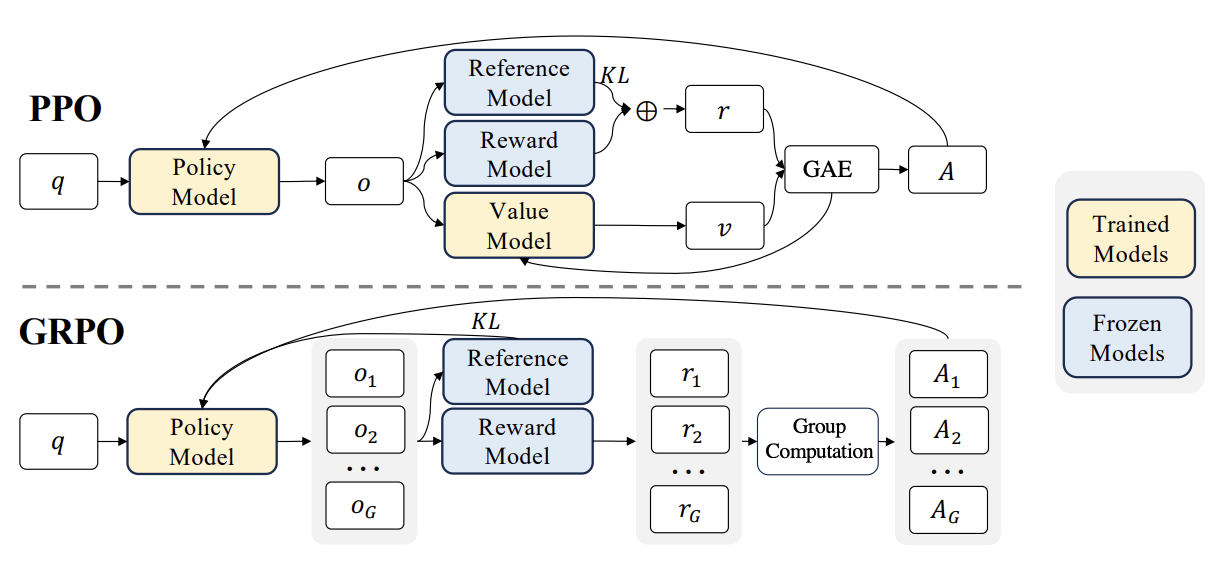

Comparison of PPO and GRPO architectures showing the removal of the critic network

Comparison of PPO and GRPO architectures showing the removal of the critic network

The Core Idea

Standard PPO uses an actor-critic architecture where the critic (value function) estimates expected rewards to reduce variance in policy gradients. However, the critic is memory-intensive and adds training complexity. GRPO replaces it with group-based advantage estimation.

Algorithm:

- Sample outputs per prompt (typically , range 16-128)

- Evaluate each output (e.g., check math correctness)

- Compute group-relative advantage:

- Update policy using standard policy gradient

Advantages: No critic network (saves memory, simplifies training); group normalization reduces variance without a value function; ideal for outcome-based rewards in verifiable tasks (math, code).

Results: DeepSeekMath 7B achieved 51.7% on MATH benchmark (approaching GPT-4/Gemini-Ultra) and 60.9% with self-consistency over 64 samples. Key: 120B math tokens from Common Crawl + GRPO fine-tuning.

When to Use: Outcome-based rewards (math correctness, code execution, game scores); memory constraints (large models where critic doesn't fit); simpler pipeline (fewer hyperparameters than PPO).

When PPO Wins Over GRPO: Preference-based tasks (human feedback); complex reward shaping (fine-grained credit assignment); online learning scenarios.

Production Adoption: DeepSeek-R1 (reasoning capabilities), Qwen-QwQ (Qwen's reasoning model), Kimi. Proven effective for training reasoning models at scale.

Rule-Based Rewards (RBR)

References: DeepSeek-AI [6], Mu et al. [16], Lyu et al. [17]

While outcome rewards (correctness) are the primary signal for reasoning models, production systems augment them with rule-based rewards to enforce desirable behaviors.

RBR are programmatic checks that reward or penalize specific patterns in model outputs. Unlike learned reward models, these are explicit rules that enforce constraints.

Common RBR Categories: Format enforcers (regex for required tags, JSON schema validation, markdown formatting, penalty -0.5 to -1.0); Language consistency (detect mid-response switching, penalize language mixing, critical for R1-Zero issue); Safety constraints (block prohibited content, enforce refusal patterns, penalty -5.0+ for violations); Reasoning quality heuristics (minimum length, maximum repetition, step diversity, verification checks).

Why RBR Matter: Stability—hard constraints prevent catastrophic failures and unparseable outputs during training. Efficiency—instant regex checks vs. minutes for human evaluation. Composability—combine multiple RBR with outcome rewards: where are typically 0.1-0.5.

Production Examples: DeepSeek-R1 uses RBR for language consistency and format validation; Logic-RL [17] uses formal logic rules as rewards for mathematical reasoning; Safety-focused RBR [16] significantly improve robustness to adversarial attacks and jailbreaking.

Design Principles: Keep rules simple (complex rules are hard to debug); weight carefully (RBR should guide, not dominate outcome rewards); monitor rule violations (high rates indicate overly strict rules or poor initialization); iterate (start with critical rules, add more as failure modes emerge).

Limitations

Brittleness: Rules can be gamed. A model might satisfy the letter of the rule while violating its spirit.

Maintenance: As models improve, rules may need updating. What was necessary for a 7B model might be unnecessary for a 70B model.

Specification: Writing good rules requires domain expertise. Bad rules can hurt more than help.

Despite these limitations, RBR have become standard practice in production reasoning systems. They provide a practical middle ground between pure outcome rewards (which can be sparse) and learned reward models (which are expensive to train).

Generative Reward Models (GenRM)

References: Zhang et al. [19], DeepSeek-AI [6]

What happens when we can't verify the outcome with a compiler or calculator? We use generative verifiers.

Instead of training a scalar reward model (which outputs a single number like 0.8), we train an LLM to act as a judge. The judge:

- Reads the student model's response

- Generates a "reasoning trace" (critique) explaining why the response is good or bad

- Assigns a score based on that reasoning

Why it matters: Standard reward models are black boxes—we don't know why they scored something high. GenRMs force the reward signal to be interpretable. DeepSeek and others use this to verify reasoning steps in domains where simple rule-based checks fail (e.g., essay quality, creative problem-solving, open-ended reasoning).

In practice: The generative verifier acts as an LLM-as-a-Judge during RL training, providing both a score and an explanation. This is particularly useful for distillation and data synthesis, where you need to understand why certain reasoning paths are better.

DeepSeek-R1

References: DeepSeek-AI [6]

DeepSeek-R1 demonstrated something remarkable: reasoning capabilities can emerge from reinforcement learning without extensive human-labeled reasoning trajectories.

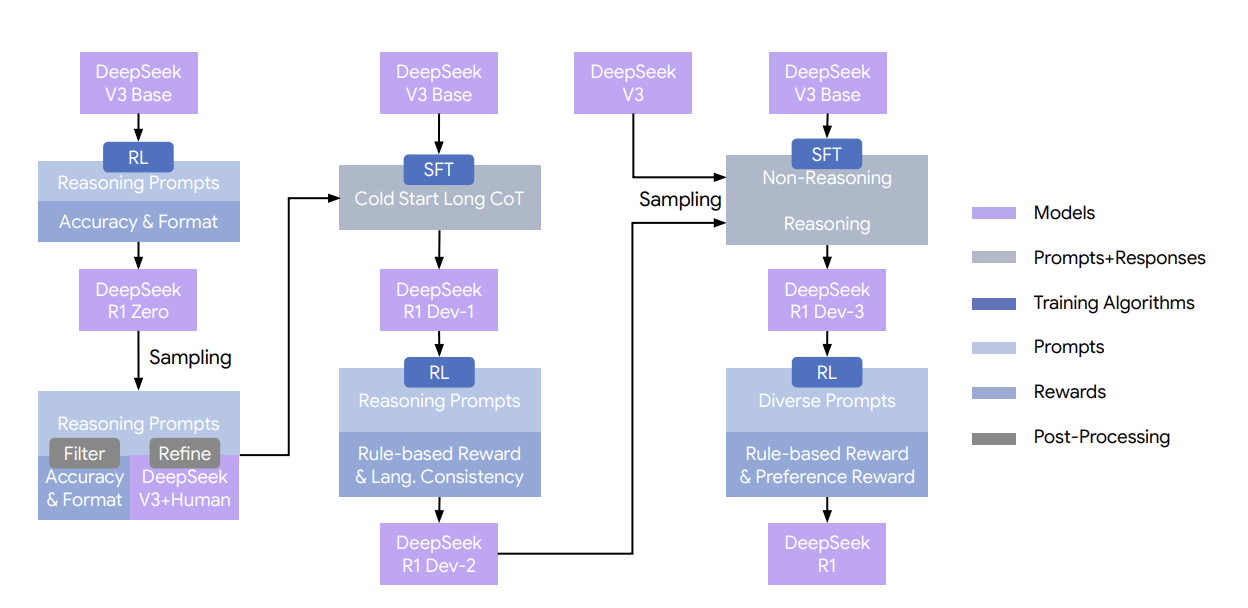

DeepSeek-R1 training pipeline showing cold start and RL phases

DeepSeek-R1 training pipeline showing cold start and RL phases

Previous reasoning models (like OpenAI's o1) required extensive human demonstrations of chain-of-thought reasoning. DeepSeek-R1 showed a more efficient path.

Training approach:

- Start with a strong base model (DeepSeek-V3)

- Cold start phase: Use a small amount of high-quality chain-of-thought examples to stabilize training and prevent collapse issues (language mixing, repetition)

- Apply GRPO with simple correctness rewards (right answer = +1, wrong = 0)

- Let reasoning patterns emerge naturally

The Cold Start Challenge: While DeepSeek-R1-Zero was trained with pure RL from scratch, it suffered from training instabilities—language mixing, readability collapse, and format violations. The production DeepSeek-R1 addresses this with a "cold start" approach: a few thousand examples of well-formatted reasoning traces that teach the model how to format its reasoning (not how to reason). This provides guardrails that constrain the format space, allowing RL to focus on improving reasoning quality rather than discovering basic formatting conventions. This has become standard practice for training reasoning models.

Emergent Capabilities: DeepSeek observed several emergent behaviors from RL training after cold start: self-reflection (checking own work), verification (validating intermediate steps), dynamic strategy adaptation (trying different approaches when stuck), and "aha moments" (recognizing the right path mid-generation). These patterns weren't explicitly programmed—they emerged from the training process.

Results: DeepSeek-R1 matched OpenAI's o1-preview on mathematical reasoning benchmarks despite simpler training. Excels at mathematics (MATH, GSM8K, AIME), coding competitions (Codeforces, LeetCode), and STEM reasoning tasks.

Distillation: Once trained, reasoning capabilities can be distilled into smaller models by generating reasoning traces from the large model and fine-tuning smaller models on these traces, enabling lower-cost deployment.

Hybrid Approach: Process Supervision

References: Lightman et al. [7]

This OpenAI work compared process supervision (rewarding each step) with outcome supervision (rewarding only final answers).

Train two reward models:

- Outcome-based: Trained on final answer correctness

- Process-based: Trained on step-by-step correctness (800K human labels)

Then use each to train policies via RL.

Process supervision significantly outperformed outcome supervision on the MATH dataset. The process-supervised model solved 78% of problems from a representative test subset.

Why Process Supervision Works

- Better credit assignment: Knows which steps were correct/incorrect

- Prevents reward hacking: Can't get lucky with a right answer from wrong reasoning

- More reliable: Catches errors early in the reasoning chain

- Interpretable: Can see where the model went wrong

However, process supervision requires labeling intermediate steps—much more expensive than just labeling final answers. OpenAI released PRM800K, a dataset of 800,000 step-level labels, to support research.

The work also showed that active learning significantly improves process supervision efficiency. Instead of randomly labeling steps, focus on steps where the model is uncertain.

The Modern LLM Stack

By recent years, a clear pattern has emerged for training state-of-the-art reasoning models. Rather than treating cold start, rule-based rewards, and iterative optimization as separate techniques, production systems combine them into a unified workflow.

This "modern recipe" synthesizes lessons from DeepSeek-R1, Llama 3, and the broader shift toward iterative methods. Here's how the pieces fit together:

Stage 1: Cold Start with Long CoT Data

Purpose: Establish stable reasoning format before RL training begins.

What you do: Collect or generate a small dataset (1K-10K examples) of high-quality chain-of-thought reasoning focused on format, not correctness. Include examples with consistent language, clear step-by-step structure (e.g., <think>...</think> tags), verification steps, and self-correction patterns.

Critical for reasoning models: If you want the model to learn self-correction during RL, the cold start data must include failed attempts and backtracking. Perfect, straight-line reasoning teaches format but makes it harder for RL to learn error recovery. Include examples like "Wait, that's wrong because..." or "Let me try a different approach..."

Why it matters: Without initialization, pure RL training collapses into unreadable outputs (see DeepSeek-R1's cold start challenge). The cold start provides guardrails that constrain the format space, allowing RL to focus on improving reasoning quality.

Implementation: Standard supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on the CoT dataset. Typically takes a few hours on a single node.

Stage 2: Rule-Based Rewards During RL

Purpose: Enforce format constraints and prevent training collapse during RL optimization.

What you do: Augment outcome rewards (correctness) with programmatic checks for format enforcement, language consistency, quality heuristics, and safety constraints. See the Rule-Based Rewards (RBR) section for detailed categories and examples.

Why it matters: RBR provide immediate feedback without human labeling, preventing catastrophic failures while guiding the model toward desirable behaviors.

Design principle: Keep rules simple and weighted low (0.1-0.5x the outcome reward). Rules should guide, not dominate. If rule violations are frequent, the cold start data needs improvement.

Alternate Stage for Assistants: Constitutional AI

Purpose: For general assistants (not reasoning models), Constitutional AI offers a scalable alternative to traditional human feedback.

What you do: Instead of collecting expensive human preferences, define explicit principles (a "constitution") and use the model itself to generate training data:

- Critique → Revision: The model critiques its own responses based on constitutional principles, then revises them. Fine-tune on the improved responses.

- RLAIF: Generate response pairs, have an AI evaluator judge which better follows the constitution, train a preference model from these AI preferences.

- Proceed to RL: Use the AI-trained preference model in Stage 3 (PPO/DPO)

Why it works: AI feedback is cheaper, perfectly consistent, and transparent (explicit principles). Claude uses this approach for scalable, principle-based alignment.

When to use: Choose Constitutional AI for chatbots when you need transparent alignment, fast iteration, and can articulate clear principles. Use traditional RLHF when tasks are highly subjective or you have abundant human feedback.

Stage 3: Iterative Optimization

Purpose: Continuously improve both reasoning quality and the training signal itself.

What you do: Instead of training on a fixed dataset (offline), generate fresh data from the current policy and iterate. For reasoning models, use GRPO with outcome + rule-based rewards. For general alignment, use Iterative DPO with reward model or LLM-as-a-Judge scoring (see Iterative DPO section for details).

Why it matters: Offline training suffers from distribution shift—as the policy improves, it drifts from the static training data. Iterative methods allow the model to explore, self-correct, and improve both its outputs and its ability to evaluate quality.

When to Deviate

This recipe is optimized for reasoning models with verifiable outcomes. For other use cases:

- General instruction-following: Skip cold start, use standard SFT → DPO/PPO

- Safety-critical alignment: Add Constitutional AI principles and process supervision

- Limited compute: Use offline DPO instead of iterative methods

- Preference-based tasks: Replace outcome rewards with learned reward models

Production Considerations

- Online vs Offline RLHF: Online RLHF continuously generates new data from the current policy with fresh feedback (used by ChatGPT, Claude), while offline RLHF trains on fixed datasets—simpler but can overfit.

- Production Metrics: Monitor reward model health (distribution drift, preference agreement), policy performance (KL divergence, win rate), and safety (refusal rates, jailbreak attempts, toxic outputs).

- Rejection Sampling: Sample N outputs (16-64), score with reward model, return best—provides inference-time alignment without training but costs N× at inference.

- Alignment Tax: RLHF can hurt performance on some tasks (<1-2%) as model shifts from pre-training distribution. Mitigate with PPO-ptx, careful KL tuning, and monitoring.

- Reward Hacking: Models exploit reward model weaknesses (verbosity, high-scoring phrases). Prevent with ensemble models, adversarial training, iterative updates, and process supervision.

- Scaling Laws: More preference data improves quality with diminishing returns. Larger reward models are more robust. Policy size matters more than reward model size. Online learning scales better.

Techniques Simplified: What to use?

DPO: Start here for first-time alignment on 7B-70B models with clean preference data and limited compute (<100 GPU-days). Simple, stable, but may not achieve absolute best performance.

RLHF (PPO): Upgrade when you need maximum control, have 70B+ models, can invest in online learning infrastructure, or have safety-critical applications. Requires significant engineering investment.

GRPO: Use for math, coding, or verifiable domains with outcome-based rewards. Memory-efficient alternative to PPO, but not suitable for preference-based alignment.

Constitutional AI: Adopt when you need transparent, auditable alignment and want to scale beyond human feedback bottlenecks. Requires careful principle design.

Process Supervision: Implement for reasoning models where reliability matters more than speed and you can afford step-level human labels. Expensive but produces interpretable reasoning.

Budget guide: <10 GPU-days (DPO only), 10-100 (DPO → PPO refinement), 100-1000 (full RLHF), 1000+ (RLHF + process supervision).

| Dimension | RLHF (PPO) | DPO (Offline) | Iterative DPO | GRPO | Constitutional AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Stages | 3 (SFT → RM → PPO) | 1 (direct) | Multiple iterations | 2 (SFT → GRPO) | 2 (SL → RLAIF) |

| Reward Model | Explicit | Implicit | Implicit or LLM-as-Judge | Not needed | AI-based |

| Stability | Moderate | High | High | High | High |

| Memory | High (actor+critic+ref) | Low | Low-Medium | Medium (actor+ref) | Medium |

| Hyperparameters | Many (10+) | Few (2-3) | Few (3-5) | Medium (5-7) | Medium |

| Iteration Speed | Slow | Fast | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Best For | General alignment | Simple tasks | Bridging stability & performance | Math/code | Safety-focused |

| Complexity | High | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Production Use | Frontier labs | Initial alignment | Llama 3, open-source | Reasoning models | Claude |

Further Developments

Hybrid RL Approaches: Leading labs combine multiple methods—initial DPO for broad alignment → targeted PPO for safety-critical behaviors; GRPO for reasoning → DPO for instruction-following; Constitutional AI principles + process supervision for interpretable safety.

Inference-Time RL: Test-time compute scaling (popularized by o1) is becoming standard with dynamic compute allocation based on problem difficulty, mixture of shallow and deep thinking, and early stopping when confidence is high.

Multi-Objective Reward Modeling: Moving beyond scalar rewards with separate reward heads for helpfulness, harmlessness, and factuality; Pareto-optimal policies balancing multiple objectives; and user-controllable trade-offs at inference time.

Agentic RL: RL methods extending beyond static responses to include tool use (code execution, web search) integrated into RL loops, multi-step planning with intermediate verification, and learning from interaction traces rather than just completions.

Open Problems

-

Reward Model Limitations: Current models struggle with distribution shift, ambiguous preferences, and capturing nuanced human values in scalar rewards. Future directions include multi-objective reward models (separate dimensions for helpfulness, harmlessness, factuality), uncertainty-aware models, and ensembles for robustness.

-

Scalable Oversight: As models become more capable, humans struggle to evaluate outputs on tasks we can't solve ourselves. Approaches being explored include debate (models argue, humans judge), recursive reward modeling (using aligned models to evaluate others), and process supervision on verifiable steps.

-

Reasoning Generalization: Current reasoning models excel at math and code but struggle with open-ended reasoning, multi-step planning in ambiguous domains, and subjective topics. Challenge: How do we extend outcome-based RL beyond verifiable domains?

-

Efficiency: RL training is expensive—RLHF requires multiple models, online learning needs continuous data collection, and process supervision requires step-level labels. Future directions include more efficient algorithms (DPO showed one path), better sample efficiency (active learning, curriculum learning), and distillation to smaller models.

-

Safety and Robustness: Models can be jailbroken, aligned behavior may not transfer to new domains, and models find loopholes in reward functions. Research areas include adversarial training, uncertainty quantification for safe deployment, and interpretability tools for understanding alignment.

-

Multi-Modal Alignment: Most RL work focuses on text, but models are increasingly multi-modal. Open questions: How do we collect preferences for images, video, audio? How do we verify outcomes in creative domains? Early work includes RLHF for text-to-image models (Stable Diffusion, DALL-E) and multi-modal Constitutional AI.

Key Takeaways

-

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) is the foundation of modern LLM alignment, using a 3-stage process: supervised fine-tuning, reward model training, and PPO optimization. A 1.3B parameter model with RLHF can outperform 175B models without it—alignment matters more than scale.

-

Constitutional AI scales alignment through AI feedback instead of human labels, using explicit principles to guide model behavior. This approach is more transparent, consistent, and scalable than pure human feedback.

-

DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) eliminates the reward model and RL complexity by deriving the optimal policy in closed form, reducing alignment to a simple binary cross-entropy loss. It's simpler, more stable, and powers most open-source models.

-

GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization) removes the critic network from PPO, using group sampling for advantage estimation instead. This memory-efficient approach is ideal for outcome-based tasks like math and coding, powering DeepSeek-R1 and similar reasoning models.

-

Outcome-based RL vs preference-based RL: For verifiable tasks (math, code), outcome rewards (correctness) are more effective than preference learning. For general alignment (helpfulness, safety), preference-based methods remain essential.

-

Process supervision rewards intermediate reasoning steps rather than just final answers, leading to more reliable reasoning and preventing reward hacking. It significantly outperforms outcome supervision but requires expensive step-level labeling.

-

Online vs offline RLHF: Production systems use online learning with weekly updates to reward models and policies. Offline training on fixed datasets is simpler but less effective at maintaining quality over time.

-

Reward hacking is a persistent challenge where models exploit weaknesses in reward models. Mitigation strategies include ensemble reward models, iterative updates, process supervision, and human-in-the-loop auditing.

-

The alignment tax (performance degradation on some tasks) is usually small (<1-2%) and can be mitigated through PPO-ptx (mixing pre-training data), careful KL tuning, and monitoring diverse benchmarks.

-

Method selection guide: Use RLHF/PPO for maximum control and complex alignment; DPO for simplicity and smaller models; GRPO for reasoning tasks with verifiable outcomes; Constitutional AI for transparent, principle-based alignment.

-

Reasoning models (o1, DeepSeek-R1) use outcome-based RL with verifiable rewards. DeepSeek observed emergent capabilities like self-reflection, verification, and dynamic strategy adaptation. While DeepSeek-R1-Zero used pure RL, production DeepSeek-R1 uses a "cold start" with small amounts of high-quality CoT data to prevent training collapse before RL takes over.

-

Test-time compute scaling is unique to reasoning models: they can trade inference compute for accuracy by generating and verifying multiple reasoning traces, unlike traditional LLMs where more compute doesn't improve quality.

-

Distillation from reasoning models enables transferring reasoning capabilities to smaller, faster models by fine-tuning them on traces generated by larger reasoning models—making reasoning more accessible and cost-effective.

-

Industry adoption patterns: RLHF/PPO dominates frontier labs (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google); DPO powers open-source (Llama, Mistral); GRPO enables reasoning models (DeepSeek, Qwen); Constitutional AI is Anthropic's signature approach.

-

Open problems remain: Scalable oversight for superhuman tasks, reasoning generalization beyond verifiable domains, multi-objective alignment, efficiency improvements, adversarial robustness, and multi-modal alignment are active research areas.

References

-

Ouyang, L., et al. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. NeurIPS 2022.

-

Bai, Y., et al. (2022). Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback. arXiv:2212.08073.

-

Bai, Y., et al. (2022). Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. arXiv:2204.05862.

-

Rafailov, R., et al. (2023). Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model. NeurIPS 2023.

-

Shao, Z., et al. (2024). DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models. arXiv:2402.03300.

-

DeepSeek-AI (2025). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv:2501.12948.

-

Lightman, H., et al. (2023). Let's Verify Step by Step. arXiv:2305.20050.

-

Xu, H., et al. (2024). Is DPO Superior to PPO for LLM Alignment? A Comprehensive Study. ICML 2024.

-

Wang, Y., et al. (2024). A Comprehensive Survey of LLM Alignment Techniques: RLHF, RLAIF, PPO, DPO and More. arXiv:2407.16216.

-

OpenAI (2024). Learning to Reason with LLMs. OpenAI Blog.

-

OpenAI (2024). OpenAI o1 System Card. Technical Report.

-

Anthropic (2023). Collective Constitutional AI: Aligning a Language Model with Public Input. Anthropic Research.

-

Yuan, W., et al. (2024). Self-Rewarding Language Models. ICML 2024.

-

Pang, R. Y., et al. (2024). Iterative Reasoning Preference Optimization. arXiv:2404.19733.

-

Dong, H., et al. (2024). RLHF Workflow: From Reward Modeling to Online RLHF. Transactions on Machine Learning Research.

-

Mu, J., et al. (2024). Rule Based Rewards for Language Model Safety. NeurIPS 2024.

-

Lyu, D., et al. (2025). Logic-RL: Reinforcement Learning with Logical Constraints for Mathematical Reasoning. arXiv:2502.14768.

-

Meng, Y., et al. (2024). SimPO: Simple Preference Optimization with a Reference-Free Reward. arXiv:2405.14734.

-

Zhang, L., et al. (2024). Generative Verifiers: Reward Modeling as Next-Token Prediction. arXiv:2408.15240.